Fred Barr

Fred Barr

1882 - 1940

By Eric Swab

Used by permission of the Old Colorado City Historical Society

I have always considered Fred Barr the benevolent benefactor of Pikes Peak hikers. He is credited with single handedly building the famous trail from Manitou Springs to the summit of Pikes Peak that bares his name. It is clear that he loved the mountains; however, his motivation for building trails was a combination of that admiration and his entrepreneurial spirit.

Fred was born in Arkansas in June of 1882 to William M. and Mary Wade Barr, the eldest of 6 children. All of his siblings were girls.[1] He came to Colorado with his family in 1893[2] when he was 11 years old. By 1900 we find Fred living with his family in Colorado City (now the Westside of Colorado Springs).[3]

Fred’s maternal grandfather Joel H. Wade had settled at the foot of Cheyenne Mountain on the Cripple Creek stage road in 1885. The Cripple Creek stage stopped at Wade’s place during the mining camp’s boom days.[4] It is said that young Fred liked to hitch rides on those stage coaches headed into the mountains.[5] These experiences must have been quite a thrill for a Kansas boy, and undoubtedly contributed to Fred’s appreciation of Pikes Peak.

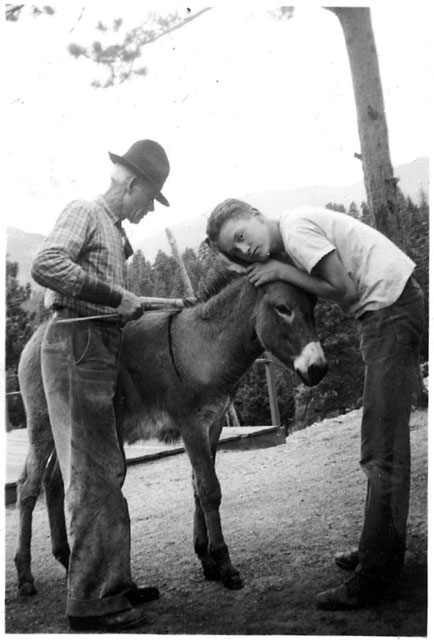

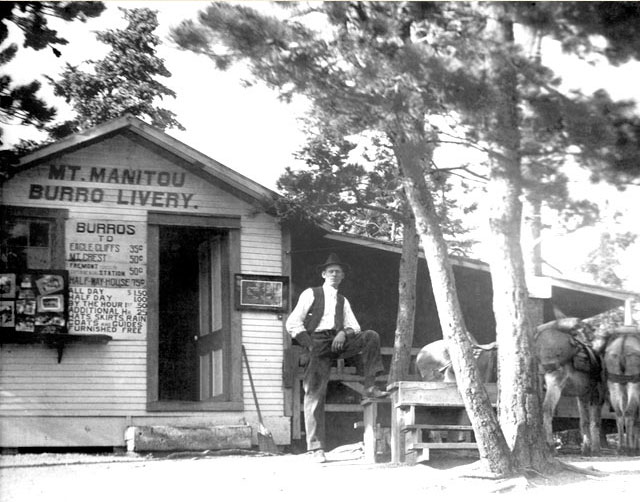

The Burro Livery Business

By 1900 the City Directory for Colorado City lists William Barr & Son, proprietors of burros & tourist carriages on the north side of Manitou Rd, West End. That same year, Fred Barr, at age 18, is listed as a driver at the Garden of Gods station, residing on the north side of Colorado Ave.. The “Garden of the Gods Station” was a streetcar stop on the Colorado Springs and Interurban Railway, where tourists disembarked to visit the Garden of the Gods.

By 1904 the Directory places their business at 1203 Colorado Avenue in Colorado City[6]. After Colorado City became part of Colorado Springs in 1917 the address became 3204 West Colorado Avenue, which puts them at the corner of Colorado and 32nd Street in the current parking lot for the Safeway super market. The family continued to live there until 1925, 3 years after William’s death in 1922[7].

The livery business must have enjoyed some measure of success. Dorothy, a travel writer for the “Young Woman’s Journal”, thought highly of Barr’s business. She wrote, “Half way between Colorado Springs and Manitou is Barr’s carriage station. … There is an opposition stand on the other side, so be sure to get the right one. Mr. Barr’s was the first Garden of the Gods station. He began with one team which he drove himself. Now he has a plentitude of fine teams and excellent drivers, and a goodly number of dear, willing, pathetic little burros. Hack drivers do take advantage of tourists in spite of the fixed rates. This Mr. Barr never does. He has worked hard to become a fixture and he wishes to keep his business straight and right. And just as we went regularly to Barr’s, we called regularly for Mr. Taylor to drive us. For I am quite sure that these two men made our drives so much more interesting than any one else would have done.”[8]

The prices charged by the Barrs for some of the points of interest that Dorothy encouraged her readers to visit were the Garden of the Gods, 50 cents, Glen Eyrie, 25 cents more, the High Drive, a 6 hour drive costing $1.25 and Williams Canyon $1.00. In her view the $1.00 fee for the Cave of the Winds was, “too high. Fifty cents would be ample.”

Not everyone thought Barr’s burros were “pathetic”. On September 15, 1908 the “Burro station … shipped a year-old burro to Mrs. R. S. Morris of Ashville, NC. The burro’s name was Miss Pike. Mrs. Morris was a tourist in this region during the summer and became infatuated with the “Rocky Mtn. canaries”, so she wanted one sent to her after her return.”[9]

Not everyone thought Barr’s burros were “pathetic”. On September 15, 1908 the “Burro station … shipped a year-old burro to Mrs. R. S. Morris of Ashville, NC. The burro’s name was Miss Pike. Mrs. Morris was a tourist in this region during the summer and became infatuated with the “Rocky Mtn. canaries”, so she wanted one sent to her after her return.”[9]

The business was not without its problems, however. In December of 1902 a man named James Kinney, “while under the influence of a powerful quantity of powerful whisky”, took possession of the “Barr burro stand”. The takeover was temporary and Kinney was sentenced to 5 days in jail[10].

The press carried a number of accounts of disagreements between employees of Barr’s livery and the burro stand across Colorado Avenue owned by Quinby. In February of 1903 William and Fred Barr were found guilty of assaulting Nelson Kvale[11]. Later that year, under the headline “Drivers of Tourist Carriages in Court”, we read that George Smith, one of William Barr’s drivers, was fined $10 and costs, on a charge of assaulting Henry Cradit[12].

Again in August of 1910 the Gazette gives this account of an altercation between the personnel of these two burro stands. No sooner had a group of women tourists, accompanied by Mr. F. Gotham, a former employee of Quinby’s burro stand, stepped off the trolley, stopped opposite the two stands, when Mr. F. M. Torrence, from Barr’s stand “made his appearance on the scene, brandishing a short club, which seems to be the approved badge of office for the solicitors of patronage at the stands, and finding himself unable to secure the ‘fares’ began a torrent of abuse which frightened the women and caused Gotham to swear out a warrant for his arrest.” According to the article this was “…not the first time… that there have been altercations between representatives of the two stands over prospective customers.”

In August of 1911 there was a repeat of the same scene with solicitors from both Barr’s and Quinby’s stands rushing a group of tourists alighting from the trolley. Each group was haranguing the tourists to use the services of their livery. When the tourists made up their minds Mr. Lawrence Bulhanan of Barr’s station started to “rough house” with Mr. Lawrence Evans of the Quinby barns. Mr.Bulhanan was fined $10.00 while charges against Mr. Evans were dismissed.

Not all judgments went against the Barrs. On September 13, 1913, William Barr was found not guilty of a “disturbance” by Justice W. H. Gowdy.[13]

Earlier that month, while driving 3 women tourists, William Barr’s carriage was struck by a streetcar. The carriage was overturned and everyone thrown out. One of the women suffered severe scalp wounds and William’s right arm was so badly broken that it had to be amputated at the shoulder.[14] Six years later, Barr sued the Colorado Springs and Interurban Railway for damages of $25,000 and won.[15]

Competition was not the only problem the Barr’s had to face. In 1913, Colorado City condemned a portion of Barr’s property for the extension of 12th Street (now 32nd). William Barr was awarded $600.00 by a jury in the district court.[16]

The timing of Fred Barr’s transition from the burro livery business in Colorado City to burro wrangler and trail builder on Pikes Peak is unclear. The Barr & Son burro stand is last listed in the City Directory of 1916. It is reasonable to assume that by this time the automobile was beginning to make inroads into the burro and carriage business. However, Fred already had a burro livery at the top of the Manitou Incline.

When the Manitou Incline Railway opened in 1908, their newspaper advertisements included the words “Pikes Peak Trip via Incline and Burro Lines, a Ten Hour Trip Only $3.00 round trip.”[17] These advertisements didn’t mention the burro operator’s name. However, a 1948 Gazette article reads, “When construction of the Mount Manitou incline railroad was begun, Barr secured the burro concession on the top of Mount Manitou.”[18] We know that Mr. Barr negotiated with the director of the Fremont Forest Experiment Station, in 1911 for pasturing his burros at the Station.[19]. Also a 1915 map of the “Mt. Manitou Park & Incline Co. Ry. Summer Resort” shows “Barr’s Corral” as part of the facilities at the top of the incline. The U. S. Census for 1920 lists Fred Barr’s occupation as “Burro Barns” at a “Summer Resort”. The 1922 City Directory lists Fred as the proprietor of the Mt. Manitou & Pikes Peak Burro Livery located at the top of the Incline.[20]

When the Manitou Incline Railway opened in 1908, their newspaper advertisements included the words “Pikes Peak Trip via Incline and Burro Lines, a Ten Hour Trip Only $3.00 round trip.”[17] These advertisements didn’t mention the burro operator’s name. However, a 1948 Gazette article reads, “When construction of the Mount Manitou incline railroad was begun, Barr secured the burro concession on the top of Mount Manitou.”[18] We know that Mr. Barr negotiated with the director of the Fremont Forest Experiment Station, in 1911 for pasturing his burros at the Station.[19]. Also a 1915 map of the “Mt. Manitou Park & Incline Co. Ry. Summer Resort” shows “Barr’s Corral” as part of the facilities at the top of the incline. The U. S. Census for 1920 lists Fred Barr’s occupation as “Burro Barns” at a “Summer Resort”. The 1922 City Directory lists Fred as the proprietor of the Mt. Manitou & Pikes Peak Burro Livery located at the top of the Incline.[20]

The 1921 Directory lists Fred W. Barr’s occupation as chauffeur. One wonders if he tried out the automobile tourist business.

The business of transporting tourists from the top of the Incline to Barr Camp and then on to the summit of Pikes Peak did not end when Fred died in 1940. Mr. Kirk Kimberlin became the owner of the Burro Livery and Barr Camp after Fred’s death.[21] The business continued to be operated by George E. “Dike” Williams from about 1954 until around 1960, after which burros no longer carried tourists up Barr Trail.[22]

Miner?

Was Fred Barr ever a miner? Several sources claim that he worked as a miner in the winter, in order to make money to build his trails[23]. There is no indication where he worked, nor at what point in his life he was a miner. On the other had another newspaper article from 1956, reads, “He operated the burro concession at the Upper Station in the summer, and spent the rest of the year working on ‘his trail’” and nothing is said about his being a miner.[24]

Barr Trail

Sometime before 1918, Fred began searching for a route up the east face of Pikes Peak to its summit. “On Christmas eve, 1918, Fred Barr set out the last pile of rocks, designating the end of the trail survey [to the summit]. It marked the completion of a task which everyone has said was impossible and impractical. Completing the survey on Christmas Eve, Fred Barr broke into the summit house, spent the night there, and returned the next day to announce his achievement. …The survey was only a beginning, the real work of building the trail was yet to be undertaken, yet it marked the realization of one of the ambitions of Barr’s life, and demonstrated unquestionably the feasibility of constructing a trail over the most scenic part of the peak.”[25]

Many sources accept 1918 as the completion date of the trail. However, it was only the “survey” that was completed and construction of a trail was to follow. From a newspaper article of June 1, 1921 we learn, “His Pikes Peak trail was completed, except for a short gap high above timberline, when snow set in last fall. It will be completed and ready for use this summer.”[26] Fred’s obituary states, “He became widely known in the region and throughout the country as the builder of the Barr trail to the summit of Pikes Peak … It was completed in 1921.”[27]

It should also be noted that the 1921 trail began at the top of Mount Manitou, (then the popular name for the top of the Manitou Incline) not from Manitou Springs. He probably adopted at least some portions of the Fremont Trail. The Forest Service paid Fred $200 to supervise the 10-man crew to build that portion of what we now call Barr Trail between Manitou Springs and No Name Creek.[28] It was built in 1917 at a total cost of $2,000.[29]

Since Barr didn’t complete his trail to the summit until 1921, what route did the “Burro Lines” use to carry tourists to the top of Pikes Peak in 1908? The Fremont Trail had been constructed in 1871 by the engineers of the Denver and Rio Grande Railway. It was named after General Fremont who spent several weeks at the springs in Manitou in 1843. It began near the lower station of the Mount Manitou Incline and went up the east shoulder of Rocky Mountain to what would become the upper terminus of the Incline and then to the top of Pikes Peak.[30] In his description of the Fremont Trail, Robert Ormes, wrote, “Above timberline people took their own route to the top.”[31] Manley Ormes goes on to say that from the Fremont Trail there “now are branches leading to French Creek and to the Bottomless Pit and to the Half Way House, on the Cog Road, over the ‘pipe line’”. The word “now” indicates they were not part of the Denver and Rio Grande trail. He is silent about who built those side trails.

The 1921 edition of Manley Ormes’ “Mountain Trails of the Pikes Peak Region” shows Barr’s Trail beginning in the town of Manitou and following a switch back route south of the incline, to Rock Creek (now No Name Creek). From there it follows the pipeline to Cabin Creek which it follows to the location of Barr Camp.

Did Fred build the trail single handedly? We have clues that suggest that he had help. We have already learned that he supervised the crew that built the trail from the town of Manitou to No Name Creek. Under the headline, “Barr Completing Pikes Peak Trail to Bottomless Pit” we read, “Workmen are now engaged in constructing a trail between the new Barr Trail to the summit of Pikes Peak and Bottomless pit. … Mr. Barr is himself now in the southern part of the state, securing additional burros for use on [his] trails...”[32] In Fred’s obituary we read that Barr trail was “being constructed under his direction.”[33] In another account, “He has secured permits from the government and most of the work he has done with his own hands.”[34] If you view Barr’s efforts as a commercial endeavor to provide places for tourists to visit on his burros, it seems likely that he would hire help to construct the trails. Whether or not he built the trails with his own hands, hikers today owe a great deal to his vision and dedication.

AdAmAn Club

On December 22, 1922 Fred and Ed Morath, convinced 3 of their hiking friends, Fred Barr, Willis Magee and Harry Standley, that they needed to do something exciting to celebrate the New Year. They settled on hiking to the summit of Pikes Peak. On December 31, 1922 they set out for the summit hiking the Cog Railway right-of-way and carrying a dozen rockets, “one-pounders”, and several dozen flares. When they arrived they broke into the summit house, (not a new experience for Fred) built a fire in the stove and thawed out. At 9:00 PM they set off a couple rockets to let the folks at home know they had made it. Then at midnight they set off the rest of their fireworks. On their return the “frozen five” decided to make this an annual tradition. They also decided to add one person to the group each year assuring that the tradition would last, and hence the group became known as the AdAmAn Club. This began a tradition that residents of the Pikes Peak region look forward to each New Years.[35]

In subsequent years they usually hiked Barr Trail starting on December 30th, spending the night at Barr Camp, and finishing the climb on December 31st. Fred was always the “first man up in the very early morning of each December 31st. He broke the ice in his creek, had coffee always hot and ready in his two gallon coffee pot so we used to call it. He never dumped the coffee grounds out of the huge pot, merely adding more coffee and more water and then setting the pot to boil on his sweet smelling pinewood burning cook stove …”.

Barr Had Grand Plans

Under the July 13, 1921 headline, “Fred Barr Asks Right to Build Road Up To Peak”, we learn that he “… is asking for a right of way up Pikes Peak and down into the Bottomless Pit from the United States government.” In this effort he had the endorsement of Colorado Governor O. H. Shoup, and Spencer Penrose and other prominent citizens of the City. This request to build a road is in addition to the, “… recently completed trail to the summit of Pikes Peak across the east slope of the mountain …”[36]

Again in 1921, the Gazette carries this story, “Fred Barr, who last year completed a burro trail to the summit of Pikes Peak, is now making surveys preliminary to the erection of a log hotel near the Mt. Manitou forestry station. [the Fremont Forest Experiment Station] The hotel will be similar to those now being used in the Glacier National park and will afford accommodation for at least 50 guests. There will be an up-to-date dining room furnished with rustic tables and chairs. In one end of the rooms will be an immense fireplace around which the guests will gather in the evening to tell stories and listen to lectures on the interesting features of the Pikes Peak region.”[37]

Barr Camp

Grand plans indeed! Neither of these came to pass, however, a rather unique hostel was constructed, higher up on the mountain at about 10,000 feet above sea level. “Unlike Any Other Camp in Mountains Is Fred Barr’s on Slopes of Pikes Peak” reads the August 6, 1922 headline. His first camp consisted of tents that would accommodate from 15 to 50 guests. The standard outing would consist of outfitting tourists at the top of the Manitou Incline with burros and supplies. At 5:00 PM he would guide them on the 2 hour trip up to the camp. A picnic supper would be served with stories around the campfire, then to bed. At 1:00 AM the next morning “…the stentorian tones of the host sound, ‘All up’ and a half-hour later the party is again gathered about the campfire, imbibing a last drink of coffee before the ascent is resumed. … The journey is so timed that the burros reach the peak summit just as the sun rises above the horizon, lighting the east in brilliant colors that gradually spread westward over the sky.”[38] These sunrise trips were continued by Fred’s successors.[39]

By 1924 Barr had built a cabin on the site, which still exists today and is still operated as a hostel for hikers wishing to rest before summitting or exploring other destinations on Pikes Peak. In 1936 Barr built two more 14’ x 24’ cabins at the camp, to accommodate visitors. That same year he announced the camp would be open in the winter.[40] One of the 1936 cabins burned down. At some time there was also a burro barn at the camp which no longer exists.

In 1930 he had plans to build a 12 foot by 14 foot cabin at about 12,000 feet. It is possible the shelter known as the “A-frame” which was built by the Forest Service in 1964[41] was built on the site of this earlier cabin.

Other Trails

Fred Barr’s mountain trail building probably started around 1908. The owners of the Manitou Incline wanted to develop the area between the top of the Incline and the summit of Rocky Mountain. They called this area Mt. Manitou Park. It contains several large boulder outcroppings which would offer Incline customers beautiful views of the plains and the surrounding mountains. To reach these points of interest Barr built trails to Mount Crest Crags, Eagle Cliff[42] and Lookout Rock. Burro rides to these observation points were offered by the Manitou & Pikes Peak Burro Livery to passengers of the Manitou Incline. The Mount Crest Crags Trail still gets some use although it gets confused with several other social trails near the summit of Rocky Mountain. The trail to Eagle Cliff (now called Eagles Nest) still exists but gets very little use.

In 1921 Barr built a trail to the Bottomless Pit from his trail to the summit. It “… will make possible a comparatively easy descent into this great pocket of a can[y]on which has always been one of the most fascinating features of …” Pikes Peak.[43] It was not the first trail to the Bottomless Pit, there having been a side trail from the old Fremont Trail.

In 1930 Barr surveyed a route to the summit of Camerons Cone. “The trip will be one from the top of Mount Manitou and the distance will be three and a half miles. He is building the trail for his own use, in order to afford more variety in burro back sightseeing. … There has never been what might be called a trail to the top, Crystal Park being the nearest approach to it. … he says he will construct a shelter halfway up and possibly put a building on the summit. Mr. Barr already has 16 miles of trail which he has built and which he himself maintains; Pikes Peak, Bottomless Pit, Halfway house, etc. … “[44]

In a 1937 story, “A trail down into ‘the crater’, the deep gash on the southeast face of Pikes Peak, has just been completed by Fred Barr… It extends from the shelter cabin he has at timberline clear down into the crater and is about a mile long. It has taken him two years to build…” Again we read, “Mr. Barr has built the trail for his own use, for burro parties, from the top of Mount Manitou and Barr’s camp, higher up on the peak. It makes 26 miles of trail that he has built … Mr. Barr now is at work on a trail into a hole known as the Second Bottomless pit, where the old Oil creek tunnel is. … The Barr trail system from the summit of Mount Manitou is the last of the trails over which burros are still used. They were in extensive use here in early days”[45]

Physically Fred Barr was of medium height, slender build, with grey eyes and light brown hair.[46] He was 46 when he married Anna Edna Williams of Colorado Springs in 1928. She was about 6 years younger than he. In 1930 they lived at 1404 South Tejon Street; by 1935 they had moved to 6 McKinley Place. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, Fred and Anna lived in a one room cabin at the top of the Manitou Incline during the summer. The cabin was divided into living and sleeping spaces by a curtain. The cabin had running water but no waste water drains. The only time that Denzil Gaskins remembers Anna coming out of that cabin was when she needed to throw out the dirty dish water.[47]

Anna sometimes accompanied Fred on the trail. “She was the first after Barr to enter the crater south of the summit on mule-back. Each year while Barr was alive she made the trip to the camp … to cook for him and his workers while they were giving the trail its spring cleaning.”[48] She was with her husband, Fred Morath and Willis Magee, on Barr trail when their burro carrying 50 pounds of dynamite slipped and fell off the trail rolling over twice. The dynamite did not explode and Fred Barr helped the animal back to his feet. They were headed to a place where a rock slide had blocked the trail.[49]

In 1940 the champion of Pikes Peak trails and burro travel left the mountain. “Fred Barr, the Pikes peak region’s outstanding trail-blazer, died from a heart attack at 11:13 a. m. Tuesday [April 2, 1940] in Willard, N. M., where he and Mrs. Barr were visiting Mr. Barr’s sister. … He and Mrs. Barr were living at 6 McKinley Place. They also spent much time at ‘Barr’s cabin, which is situated eight miles above Manitou Springs on the famous Barr trail. … Mr. Barr was 58 years old …”[50] Anna died 25 years later. She and Fred are buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Colorado Springs.

Fred’s trail to the summit was assured longevity when, in 1948, the Forest Service undertook its reconstruction. “The Barr trail to the summit of Pikes Peak from Manitou Springs is to be reconstructed and widened with machines developed in World War II. … It will almost exactly follow the course of the present trail.”[51]

On their December 1949 climb to the summit, the AdAmAn Club, began a monument in memory of Fred Barr. “At a point on the trail halfway between timber line and the summit of the peak each member of the club and each guest in the group will place a native granite rock [on the pile]. … Words were spoken in commemoration of Barr, who built the trail with his own hands unassisted” A sign that read “In memory of Fred W. Barr, builder of the Barr trail to the summit of Pikes Peak. It was thru his untiring effort and boundless vision that this trail was constructed. Erected by the AdAmAn club of Colorado Springs of which he was a charter member. January 1, 1950.”[52]

Author’s Note:

This paper relies heavily on newspaper articles, which are not always reliable. Where conflicts exist between stories I have favored the one whose date is closest to the actual event, unless a later article can be substantiated by other sources. The term Mt. Manitou occurs so many times in the references used for this paper that it must have been the accepted popular term for the peak that is immediately west of the town of Manitou Springs. That peak is named Rocky Mountain on the USGS map of the region, with Mount Manitou being the summit about ½ mile northwest of Rocky Mountain.

[1] United States Census for 1900, 1910, 1920 & 1930.

[2] Pikes Peak Atlas, 1959 edition, from an interview with Manley Ormes in 1922.

[3] 1900 Giles City Directory for Colorado Springs, Colorado City and Manitou. This is the first year that the directory included Colorado City and Manitou. Also 1900 U.S. Census.

[4] History of Pike National Forest, by Horgen Ingwals S., & Comp. Section 25 page 16, Pikes Peak Public Library.

[5] Colorado Springs Gazette, January 19, 1930, p. 13.

[6] Colorado Springs City Directory 1904

[7] Colorado Springs City Directory 1925.

[8] Young Woman’s Journal, Vol. XVII, 1906 pp. 449-451, “Letters From Dorothy, VI. Colorado Springs, August 10th”

[9] Colorado Springs Gazette, September 16, 1908, p7, col 4.

[10] Colorado Springs Gazette, December 7, 1902.

[11] Colorado Springs Gazette, February 2, 1903, Kvale is listed as a teamster in the 1901 directory.

[12] Colorado Springs Gazette, 10 September, 1903.

[13] Colorado Springs Gazette, September 13, 1913, p. 12 col. 2

[14] Colorado City Iris, September 4, 1908, p1 col 4

[15] Colorado City Iris, May 8, 1914, p.2 col. 1.

[16] Colorado Springs Gazette, February 19, 1913, p 12 col 5.

[17] Colorado Springs Gazette, July 28, 1908, p. 6 col. 5.

[18] Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, November 21, 1948.

[19] “Time Diary Fremont Experiment Station, Sept 2, 1909 to Dec 31, 1910”, entry for September 7, 1909, the Colorado State University library.

[20] 1922 Colorado Springs City Directory.

[21] Colorado Springs Gazette, October 30, 1930. Also a telephone conversation with Denzil Gaskins, June 28, 2011.

[22] An email sent by Lee Williams to Neal and Teresa Taylor, June 13, 2009.

[23] Short biography written by Jim Bates for the AdAmAn Club. “Burro Ride Up Pikes Peak” by Dorothy Aldridge, Colorado Spring Gazette Telegraph, date unknown, (This article has other errors). “Fred Barr: The Trailmaster” by Deb Acord, Colorado Springs Gazette, August 14, 2005.

[24] “Barr Trail Named for Tireless Builder of First Route Up Rugged Pikes Peak”, by Ray Colwell The Free Press, Colorado Springs December 30, 1956, p.24

[25] Colorado Springs Gazette, December 25, 1921

[26] Colorado Springs Gazette, June 1, 1921

[27] Colorado Springs Gazette, April 3, 1940.

[28] “Pikes Peak Atlas”, 1959 edition, by Robert Ormes. Fred Barr told Manley Ormes this in a 1922 interview.

[29] “Barr Trail Named for Tireless Builder of First Route Up Rugged Pikes Peak”, by Ray Colwell The Free Press, Colorado Springs December 30, 1956, p.24. This is the only place the date of 1917 appears, but certainly it was before 1922 when Manley Ormes interviewed Fred Barr.

[30] “Mountain Trails of the Pikes Peak Region”, compiled by Manly D. Ormes, 1916

[31] “Pikes Peak Atlas”, 1959 edition, by Robert Ormes.

[32] Colorado Springs Gazette, June 1, 1921.

[33] Colorado Springs Gazette, April 3, 1940.

[34] Colorado Springs Gazette, October 19, 1930., p. 1 Sec. 2

[35] There are at least 4 accounts of the first New Years ascent of Pikes Peak by 3 members of the original “Frozen Five”, Fred Morath, Harry Standley and Willis Magee. None of them quite agree on all the details, but the basic story presented here has been distilled from the four accounts. Apparently Fred and Ed Morath climbed to the summit New Years Eve of 1921. This is the year they set fire to the railroad ties, according to Fred Morath.

[36] Colorado Springs Gazette, July 13, 1921.

[37] Colorado Springs Gazette, September 19, 1921.

[38] Colorado Springs Gazette, September 6, 1922, p. 7

[39] Mr. Hess Dyas gives a first hand account of a burro trip with his dad, from the top of the Incline to the summit of Pikes Peak with an overnight stop over at Barr Camp in 1946, in an email to Teresa and Neal Taylor, July 31, 2005.

[40] “Barr Building Chalets on Peak Slopes; Opens Up New Trails In Virgin Territory”, September 20, 1936.

[41] Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, June 20, 1937, p. 1. Also an email sent by Walter Schmucker to Dave Phillipps, August 18, 2010.

[42] Colorado Springs Gazette, January 19, 1930, p.13

[43] Colorado Springs Gazette, June 1, 1921.

[44] Colorado Springs Gazette, October 19, 1930., p. 1 Sec. 2

[45] Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, June 20, 1937, p. 1

[46] Fred Barr’s World War I draft registration card.

[47] 2011, interview with Denzil Gaskins, son of the assistant engineer of the Manitou Incline.

[48] “Mrs. Fred Barr Hopes to Add Rock to Memorial Cairn”, Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, December 31, 1949.

[49] Colorado Springs Gazette, June 24, 1930, p.7 col.6

[50] Colorado Springs Gazette, April 3, 1940, p. 1

[51] Colorado Springs Gazette, November 21, 1948.

[52] Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, December 29, 1949.