With time, and the fact that some of the original “Frozen Five” had made numerous winter climbs up Pikes Peak including ascents on New Year’s Eve in years before 1922, the AdAmAn club's origin story had become somewhat convoluted and, one might even say, downright mythical. After all, this is an event that began a century ago, and the climbing members that made the trek in the early years are no longer with us. The origin of the club and many of the early stories were documented to some extent, but many, especially those that were humorous or maybe a bit ribald got passed down verbally and, over time, took on a life of their own. The oft-repeated account that grew out of these, less than accurate stories, suggested the “Frozen Five” picked up railroad flares along the Cog Railway, illicitly entered the Summit House, then made a bonfire from a pile of railroad ties to signal the city below that they had reached the summit. Club President George Lindeman, in 1965, called the 1922 AdAmAn climb “the first documented winter ascent of Pikes Peak” and later Club President Don Sanborn would state, “The AdAmAn Club is a vaunted local tradition which began with acts of theft, breaking and entering, and arson!” It was later confirmed that none of these things applied to the seminal climb in 1922. It is still believed, however, that one or more of these events likely did occur during previous, pre-club winter ascents.

In 2014, Don Sanborn and others noted that some written accounts and recollections of the early years differed considerably from the earlier documentation. Considering this fact, and with many eager to know the true formation story, a group of members and local historians decided it was time to set the record straight. What the researchers learned did indeed contrast with what the club had come to believe. The details of this newly uncovered information were equally entertaining.

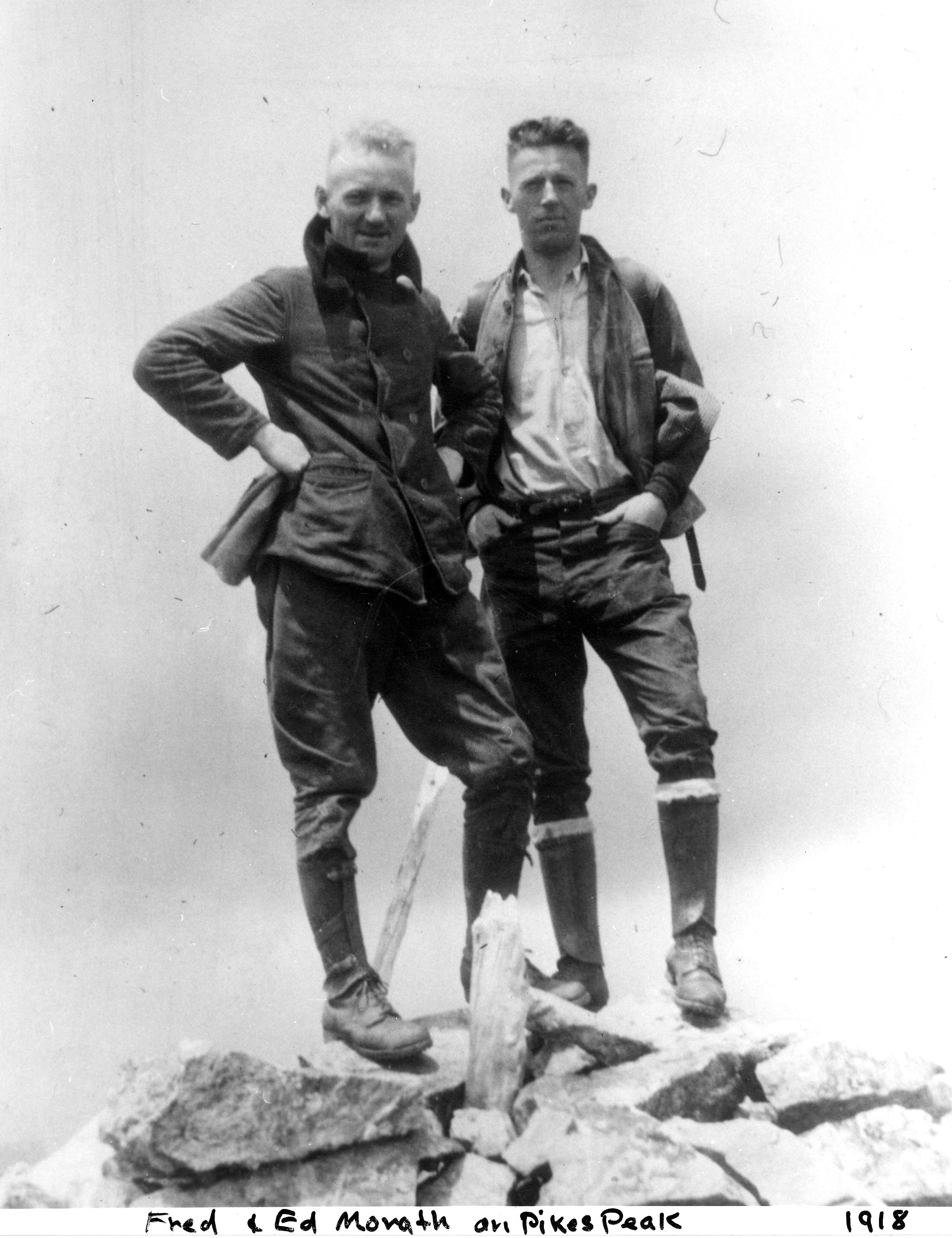

|

| Fred and Ed Morath on Pikes Peak 1918, Pioneers Museum |

Fred and Ed Morath, brothers, and Colorado Springs natives, planned the first AdAmAn climb in December of 1922. Both were skilled mountaineers and had climbed many of the major peaks of North America. Before 1922, they had ascended Pikes Peak 35 times, both in summer and winter, including the two previous years, 1920 and ‘21, on New Year's Eve. It appears the brothers hatched a new plan during their 1921 ascent, or shortly thereafter. The idea was to hold a New Year's "watch party" for the benefit of the community. The two had decided to climb Pikes Peak to again usher in the new year, however, this time would be a little different. They would pack an assortment of rockets and flares up the mountain for a "unique spectacle" the locals would never forget.

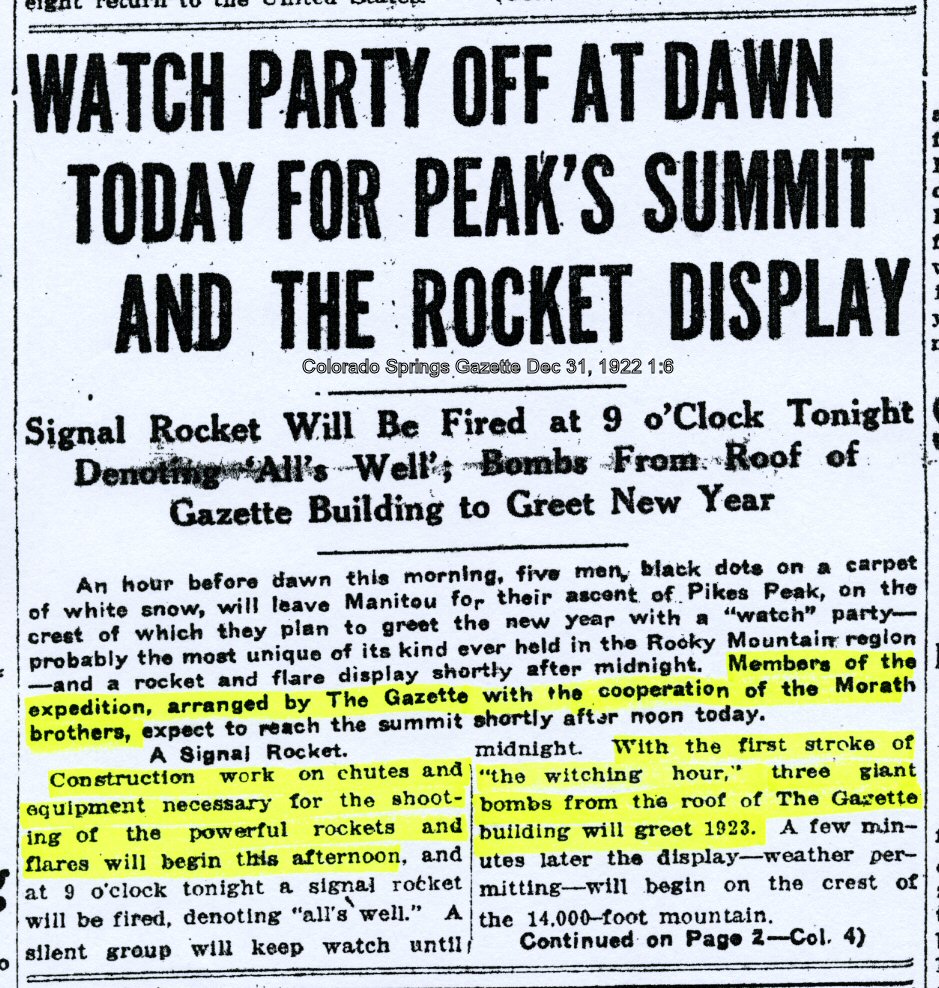

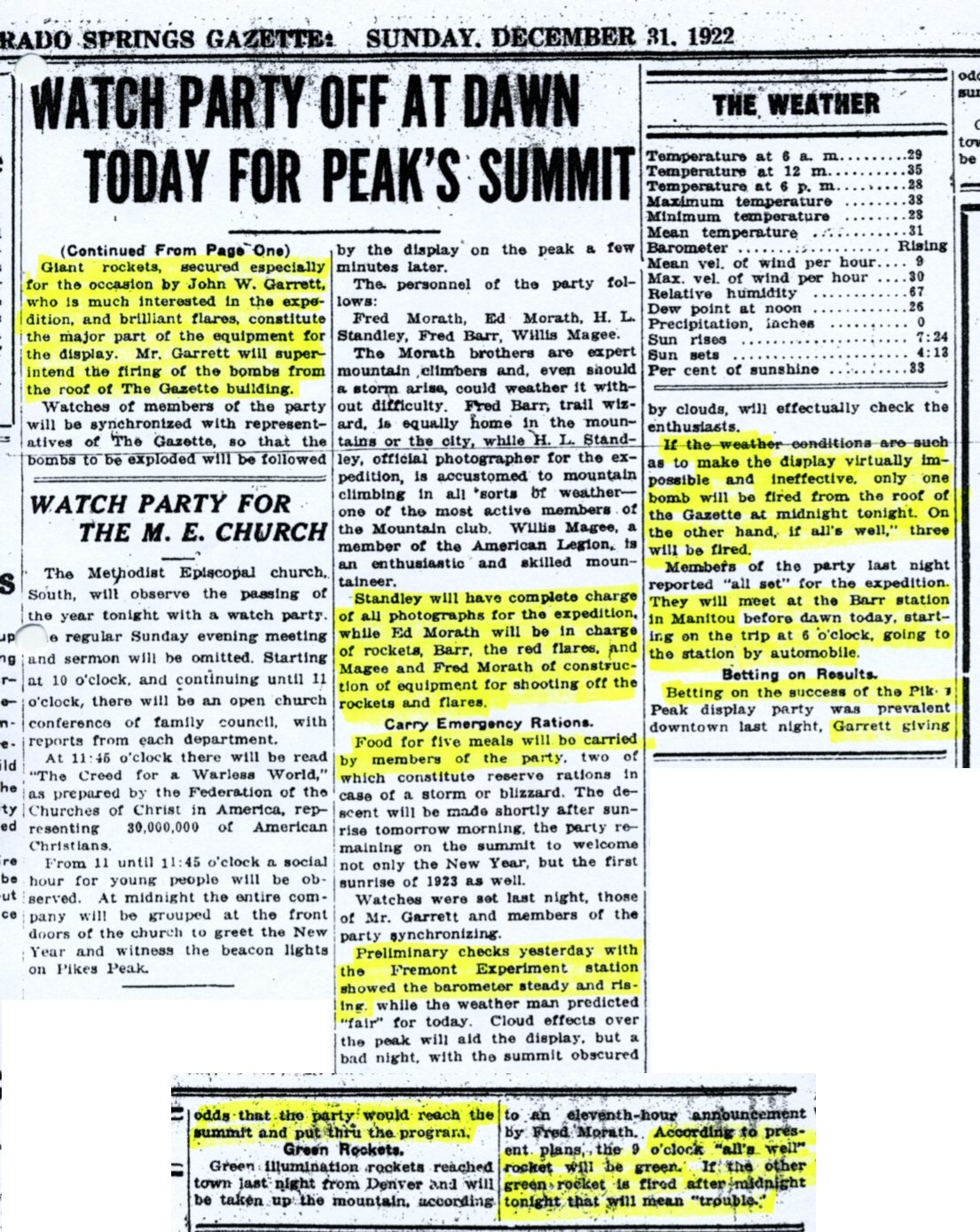

The Morath brothers arranged for the Colorado Springs Gazette to sponsor and promote the event. It would be called "The Gazette Pikes Peak Watch Party." As of December 16, 1922, the brothers and the newspaper had completed a general plan for the event. In a front-page story, the newspaper reported on the plan which included the time of departure and some flare and rocket details. By December 24, 1922, the brothers had selected the third member of the party, Fred Barr. Fred, the builder of Barr Trail, was well known locally as the "Trail wizard of the Pikes Peak region." Plans were made to add a fourth member to the climbing party. The planned route was along the Cog Railway, which didn’t operate in the winter. On or about December 22, 1922, a scouting climb reported finding snow depths along the route varied from 5 to 15 feet deep.

The fireworks for the event had been arranged by local sporting goods businessman, John W. Garrett, and arrived on December 27, 1922. As the new year approached, the reported plan expanded with Garrett doing a related firework display from the roof of the Gazette building. His "watch party” on the roof would set off two giant rockets at the stroke of midnight. Other newspapers in the state, especially those in Denver, picked up the story. The event was also attracting national interest with letters having been received from Omaha, Nebraska, Kansas City, Missouri, and as far away as New York City.

By December 28, 1922, the brothers had added the remainder of the climbing party: Harry Standley and Willis Magee. Both avid mountaineers, Willis had climbed previously with the brothers, and Harry, a noted local photographer, became the official photographer for the climb.

Permission had been received from the Stewart brothers, then in charge of the summit house, to allow access to the building for shelter. The December 28 article in the Gazette states: "The skies being clear at midnight, the flares will be lighted, rockets will pierce the heavens, and 1923 will be ushered into the Pikes Peak region in the most novel and unique manner in its history."

On December 30, the Gazette reported: "Betting on the success of the Pikes Peak display party was prevalent downtown last night, Garrett giving odds that the party would reach the summit and put thru the program." The rockets used by the club were not strictly for display but also conveyed information to those watching below. A planned nine o'clock green rocket would be fired to communicate "all is well." A second green rocket was set aside to be fired after midnight signaling "trouble."

|

| Gazette Telegraph Article, December 31, 1922, Pikes Peak Library District |

|

| Gazette Telegraph Article, December 31, 1922, subsequent pages, Pikes Peak Library District |

|

Carrying 175 pounds of powder, flares, and food, the climbing party departed Manitou Springs at 6:00 a.m. on Sunday, December 31. Following the Cog railroad tracks, the group noted a temperature of 2 below zero at the McReynolds halfway house. The temperature continued to fall and the winds increased in velocity as they climbed higher. Eight hours after starting they arrived at the summit in an exhausted state. They reported that the last two miles of their ascent took three hours to complete due to extreme winds and ice-covered stretches. The temperature at the summit was 10 below zero. At one point, the force of the wind nearly blew Willis Magee over a cliff. After completing his thirty-sixth ascent, and tenth winter ascent, Fred Morath told the Gazette that the blizzard surpassed anything he had ever experienced. The group was certain that, had they not had access to the summit house, they would have perished in the elements. As the day progressed, however, the weather began to clear and the group was indeed able to shoot the planned fireworks show. A green rocket was fired at 9:00 p.m. and a flare was lit. In later years, this 9:00 p.m. rocket would become a tradition of firing five rockets or flares at 9:00 p.m. to honor these original "Frozen Five" climbers. In response to the 9:00 p.m. rocket, John Garrett shot fireworks from the roof of the Gazette building and Joe Caldwell, the city electrician, dipped the city lights for 30 seconds in response to their signal.

|

| Photo of Gazette Watch Party by Harry Standley, December 31, 1922, Pioneers Museum |

Skies were clear at 11:30 p.m. Unfortunately, a few minutes later the blizzard returned, much to the consternation of the party. Though the flurry lasted only 30 minutes, ending shortly after midnight, the group chose to set off their flares and rockets in the middle of the blizzard. Though the rockets achieved heights of 500 feet above the summit, the cloud cover on the mountain kept them from being seen from below.

Ed Morath and Fred Barr were in charge of firing the rockets while the other three men lit the flares that they had placed in a semi-circle across the east face of the summit. The first of these had to be started by live coals carried from the summit house stove. Since the flares burned for some time, viewers from below saw flashing on the summit when the clouds lifted 10 minutes after midnight. After completing the display, and for the first task of the new year, the men signed the summit house register as the "Gazette Watch Party."

It continued to snow through the night and dense clouds obscured the first sunrise of the new year. The climbers began their descent back to civilization at 9:30 a.m. on New Year's Day. Arriving in Manitou at 1:30 p.m., the descent took four hours, and the group was exhausted by their battle with the elements. Having completed what would later become an AdAmAn tradition, the first climb was dubbed "probably the most unique New Year's Watch Party of its kind ever held in the Rocky Mountain region."

Noting the enthusiasm of the community, in March of 1923, the group met again to formalize the plan they had hatched in December on the summit to form an official club to carry on the climb and fireworks show annually. Fred Morath had the idea to add one man each year and call the club the Add a Man club with the spelling stylized with the 'A's representing mountains in the form "AdAmAn."

For 100 years, the club has grown, thrived and become part of the rich heritage of the Pikes Peak Region. It is a unique event in all of America. The fireworks display at the stroke of midnight gives the grand old peak a crown of jewels to start the New Year with hope and enthusiasm.

The Adaman™ Club has certainly come a long way since the club’s beginning. Still, it is good to know that in our modern time of doing things the easy way, there are still folks who love to get out at this special time of the year and carry on the tradition and heritage left to us by these men we lovingly call the “original Frozen Five”.

|

| AdAmAn Club Resting, c. 1930, Pioneers Museum |